What Lies Beneath |

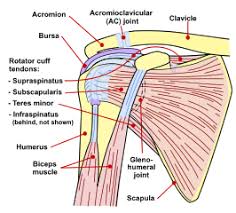

A large part of being an equipment manager is ensuring proper fit of protective equipment to minimize the risks of injury to athletes. While we cannot eliminate injuries from happening, putting players in properly fitting equipment and ensuring they wear it during practices and games may help reduce the occurrence and severity of injury. While the AEMA and major sports equipment companies provide a plethora of information on properly fitting athletes for every sport, equipment managers could benefit from an increased knowledge of anatomy and a better understanding of why protective equipment covers certain portions of the human body. Not every manager has a strong background in anatomy. The AEMA Certification Manual provides some basic information on the acromioclavicular joint (AC joint) and burners or stingers (AEMA, 2004 p. 50,52) and Jerry Fife’s 2006 AEMA Journal article “Know it to Protect it,” further explored the bones and joints of the human body. Both of these articles provide a great starting point to understanding anatomy so that we can best protect the athletes we fit, but there is a lot more to the human body than what is covered in the current literature. The purpose of this article is to expand AEMA literature on human anatomy in hopes that an increased knowledge pool will lead to better fitting equipment, and safer athletes. Though it will elaborate on some of the more important structures, it is by no means comprehensive. This article will focus specifically on football shoulder pads and the anatomy of the shoulder—the AC joint, the neck of the humerus, the rotator cuff, and the brachial plexus—and why these areas need to be protected. THE ACROMIOCLAVICULAR JOINT: WHAT IS IT? The scapula is positioned on the back of the thoracic cage and forms the glenohumeral joint with the head of the humerus, the bone of the arm. The scapula and clavicle serve as attachment points for many of the muscles that create arm movements. The strong and fibrous acromioclavicular ligament holds the two bones together and allows for normal arm movement. Damage to the AC ligament, typically sustained in a direct blow to the shoulder, can cause a weakened connection of the AC joint and lead to a decreased ability to properly move the arm (Drake, 2010). WHY PROTECT IT? The AC channel of the shoulder pad protects the AC joint. Typically this channel forms an arch over the AC joint and distributes compressive forces away from the joint itself. Equipment managers should check the manufacturer’s recommendations of each pad to make sure the AC channel fits properly to ensure the safety of the AC joint. If spider pads are employed for further protection of the AC joint, care must be taken to ensure that the AC joint falls within the gaps of the spider pads. If the padding directly covers the AC joint, the forces will not be dispersed, and instead may be directed on it. Remember to always measure the distance between AC joints first when fitting for shoulder pads. This is how you determine initial shoulder pad sizing. Adjustments can always be made for a better fit, but shell size is dependent on distance between AC joints (AEMA, 2004). THE SURGICAL NECK OF THE HUMERUS: WHAT IS IT? WHY PROTECT IT? The protection of cups varies by manufacturer and by position. Typically, skilled positions have smaller cups to allow for more movement. Linemen should have larger cups as they typically make more contact with the shoulder and upper arm during play. The AEMA Certification Manual does not specifically address cup size, but most shoulder pads provide adequate protection to this area. If you are fitting a lineman into lighter pads, check with your athletic trainer to ensure the upper part of the arm is well protected. THE ROTATOR CUFF: WHAT IS IT? WHY PROTECT IT? The arch of the shoulder pad covers the scapula and muscle bellies of the rotator cuff and the cups of the shoulder pads protect the head of the humerus where the rotator cuff muscles attach. The pads will protect the muscles from trauma from a direct blow, but there is no way for padding to protect tearing of the rotator cuff muscles or shoulder dislocations. These injuries can occur from improper technique with throwing or tackling, which can cause direct damage to the rotator cuff or put the arm in a position more prone to injury. To ensure protection from a direct blow always check to make sure the scapula and upper arm are covered (AEMA, 2004). THE BRACHIAL PLEXUS: WHAT IS IT? Because these nerves run underneath the clavicle, clavicular fractures can cause neurological damage. Burners or stingers are common injuries where these nerves are overstretched, compressed or subject to a direct blow (Drake, 2010). WHY PROTECT IT? If the clavicle becomes damaged, the brachial plexus may in turn be damaged. Keep in mind that stinger injuries will not be prevented by pads, but protecting the clavicle will aid in preventing more severe injuries due to clavicular fractures or damage. Properly fitting pads should completely cover the clavicle and redistribute direct forces away from it. Always check to make sure pads properly cover the clavicle, and that it is not exposed at the collar (AEMA, 2004). CONCLUSION Issues at the shoulder can cause deficits in function that extend down the arm and into the hand that can sideline a player on the field and in life. My hope is that by highlighting these critical structures in shoulder anatomy, equipment managers don’t just know how to fit equipment but why we fit it properly. For further anatomical information, I recommend “Gray’s Anatomy for Students,” by Richard Drake, A. Wayne Vogl and Adam W.M. Mitchell and “The Atlas of Human Anatomy,” by Frank H. Netter, MD. Jacob Manley SPT, EM,C, is a first year graduate student at Shenandoah University in Winchester Virginia. He is pursuing a dual degree—a master’s in athletic training and a doctorate in physical therapy. Jacob graduated in 2014 with a degree in kinesiology from the University of Virginia, where he worked as a student equipment manager for the football team and as a strength and conditioning intern. Jacob received his AEMA certification in June of 2014 and was a Jimmy Callaway Scholarship Award Winner. Brad Dinklocker is a second year graduate student at Shenandoah University in Winchester, VA pursing a dual degree in a master’s in athletic training and doctorate of physical therapy. Brad graduated from Shenandoah University with a bachelor’s degree in kinesiology with a focus in exercise science. He is a current member of the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) and the National Athletic Trainers’ Association (NATA). |